Difference between revisions of "A Basic Account"

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

(39) Meanwhile on Tuesday morning, as Private Joseph Clews rode east toward Cedar City from Mountain Meadows, he encountered Higbee and his contingent headed west to Mountain Meadows. Higbee ordered Clews to fall in with his unit. They arrived at the Meadows that afternoon. (40) After assessing conditions and meeting in council to deliberate, Major Higbee admitted that he returned "at once to Cedar [City]" and "reported to Major Haight that [the] emigrant company was not killed as Lee['s] express had stated the day before, but were fortified and were under a state of siege. . . ." Although Higbee did not see Colonel Dame, he conceded that the purpose of his express was "to inform Col. William H. Dame, Commander of [the] Iron Military District, [of] the conditions of things at [Mountain Meadows]." | (39) Meanwhile on Tuesday morning, as Private Joseph Clews rode east toward Cedar City from Mountain Meadows, he encountered Higbee and his contingent headed west to Mountain Meadows. Higbee ordered Clews to fall in with his unit. They arrived at the Meadows that afternoon. (40) After assessing conditions and meeting in council to deliberate, Major Higbee admitted that he returned "at once to Cedar [City]" and "reported to Major Haight that [the] emigrant company was not killed as Lee['s] express had stated the day before, but were fortified and were under a state of siege. . . ." Although Higbee did not see Colonel Dame, he conceded that the purpose of his express was "to inform Col. William H. Dame, Commander of [the] Iron Military District, [of] the conditions of things at [Mountain Meadows]." | ||

| − | == The Siege at Mid-Week == | + | == The Siege at Mid-Week == |

| + | |||

| + | During the week, Major John M. Higbee recalled, he observed that two or three militiamen were "painted like Indians." (41) At least one of the two militia camps was within sight and earshot of the emigrant camp. From that militia camp, Sergeant Samuel Pollock admitted, he and other militiamen observed Indians firing on the emigrant camp but took no action to intercede. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (42) After the sudden attack on Monday morning, September 7, the emigrants had taken defensive action to afford themselves better protection. They circled their wagons, dug holes around their wagon wheels, lowered their wagon boxes and built other crude defensive fortifications. Observing these fortifications and the Indians' ineffectual fighting on Wednesday, September 9, Major Lee reluctantly concluded that the Indians and the emigrants were at a standoff. (43) The impasse created a crisis for militia commanders. "We knew," Major Lee admitted, "that the original plan was for the Indians to do all the work, and the whites to do nothing, only to stay back and plan for them, and encourage them to do the work. Now we knew the Indians could not do the work, and we were in a sad fix." | ||

| + | |||

== The Richey Springs Incident == | == The Richey Springs Incident == | ||

==== Wednesday, September 9 ==== | ==== Wednesday, September 9 ==== | ||

Revision as of 22:24, 5 June 2011

The following narrative of the Mountain Meadows Massacre is drawn from fourteen massacre participants and other militiamen and contains more than seventy key confessions covering all aspects of the massacre. To provide context, we have also included other narration that has substantial support in the evidence. The confessional statements are numbered in parentheses ( ).

Contents

- 1 War Atmosphere and Invasion Panic in Southern Utah

- 2 Conduct of the Emigrant Train

- 3 Explosive Encounter in Cedar City

- 4 Planning Hostile Action Against the Emigrant Company

- 5 Inciting Paiute Indians to Assemble at the Mountain Meadows

- 6 The First Attack

- 7 Militia Reinforcement Sent to the Meadows

- 8 The Siege at Mid-Week

- 9 The Richey Springs Incident

- 10 Council Meeting at Mountain Meadows

- 11 The Final Massacre

- 12 The Aftermath of the Massacre

- 13 How Reliable are these Confessions?

War Atmosphere and Invasion Panic in Southern Utah

August 16 - September 11, 1857

(1) Many Iron County militiamen admitted that in the late summer of 1857, the approaching federal army commanded by Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston created a profound sense of crisis.

(4) Major John M. Higbee admitted that the militia undertook extensive militia preparations as they considered the best means of "defending ourselves and families against the approaching army." They looked for places of refuge "in case we had to burn our towns and flee to the mountains." Then they dispatched patrols to "prevent any portion of the army from approaching." Speaking of "their endeavors to protect themselves and families from Mob Violence," Major Higbee admitted that people spoke of "Buchanan's Army" as "a mob." Higbee also conceded that local settlers "had to be good friends with the Indians at all hazards" so that "they could be used as allies should the Necessity come to do so."

Major Isaac C. Haight of the military district's 2nd Battalion revealed his bellicose intention when he declared that he would not wait for orders from headquarters in Salt Lake City but his battalion would attack the dragoons "and use them up before they got down through the canyon."(5) The threatening atmosphere created by the invasion excitement fanned the fears of an overzealous element within the Iron Military District. Ignoring later legends perpetrated by the purveyors of a sensationalist crime genre that fed on the massacre, there is still ample evidence that even other Mormons perceived this element as a threat to their own safety. In a reminiscent account, Major John M. Higbee avowed that during the "Buchanan or Mormon War" there was among some "a craze of fanaticism stronger than we would be willing now to admit."

Major John D. Lee was one of these. (6) Believing as he did that the Mormons were "at war with the United States," Major Lee of the militia's 4th Battalion opined that it was "the will of every true Mormon in Utah . . . that enemies of the Church should be killed as fast as possible."

Conduct of the Emigrant Train

As we shall see, some settlers in Cedar City accused the Arkansas emigrants of provocative acts. Therefore, it is relevant that other Mormon militiamen from the same military district had encounters with the emigrants that involved no such behavior. Their numerous encounters were at least civil if not cordial. Consider these:

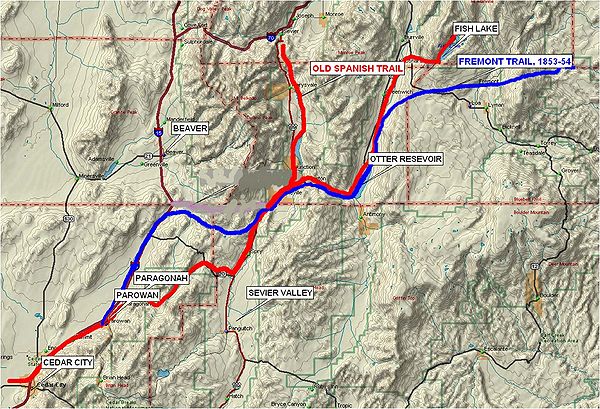

In the evening of August 24, the George A. Smith party met the emigrant train at Corn Creek, about one hundred miles north of Cedar City. Besides Smith, his party included Jacob Hamblin and Thales Haskell of Fort Clara (Santa Clara), Silas Smith of Parowan, and Philo T. Farnsworth and Elisha Hoops of Beaver. Jacob Hamblin would later opine that some emigrant men were "rude and rough and calculated to get the ill will of the inhabitants." Yet Hamblin described his own conversations with them as ordinary trail talk about grass, water and other trail conditions without any unpleasantness. Personally, he found them to be "ordinary frontier homespun people, as a general thing."Testifying in the 1875 Lee trial, Silas Smith noted that when some of the emigrant men asked if the Indians would eat a dead ox that lay nearby, it "created suspicion that they would play foul games by some means." Some of them also said "By God!" and similar expressions. They were a "rough lot of people," thought Silas, although he acknowledged that "I could not say that they were a rough set of fellows, but that was my opinion." But as we will see, his reservations were minor. He had two later encounters, each one amicable.

The experiences of many others were similar. Mormon settler John Hawley maintained that he traveled with the Arkansas train for part of three days. Silas Smith saw them again just north of Beaver and "took supper" with them. In Beaver, Edward W. Thompson and Robert Kershaw watched them pass without untoward incident. A hearsay account maintains that John Morgan of Beaver traded a cheese to an emigrant. Traveling south to Red Creek (Paragonah) Silas Smith visited them for the third and last time. A half a dozen miles ahead at Parowan, Jesse Smith traded salt and flour to them. A hearsay account says that Alfred Hadden of Parowan traded them a cow that Hadden was running at Shirt's Creek below Cedar City.

Below Cedar City, the accounts are similar. Near Fort Hamilton, John Hamilton Jr. delivered a cow to them to complete the trade with Alfred Hadden. As the company approached the hamlet of Pinto in the evening of Friday, September 4, Joel W. White and Philip Klingensmith passed them on horseback going and returning without incident.

Entering the Mountain Meadows on Saturday evening, September 5, militia private David Tullis observed that they were a "large and respectable-looking company" who "behaved civilly." Samuel Knight and Carl Shirts met them farther down valley. In a statement attributed to Carl Shirts, they were "perfectly civil and gentlemanly."

Thus, contrary to much later rumor and hearsay, credible accounts demonstrate that during the journey from central Utah into the south, local settlers had a remarkable number of encounters with the emigrant train that they would have characterized as civil.

Explosive Encounter in Cedar City

Around Thursday, September 3

But in Cedar City invasion fears were peaking. The result was that perceptions of the passing emigrants were warped by the fog of war. There are a variety of accounts, some first-hand and many second-, third- and fourth-hand, with many contradictions and some obvious exaggerations. What the first-hand accounts have in common is this: Disputes arose in Cedar City among emigrants and settlers over trading and sales; one or more emigrants used profane and threatening speech, possibly toward an elderly Mormon woman; to provoke the Mormons, one or more emigrants may have boasted of killing the Mormon founder Joseph Smith some years before; and, when the local marshal intervened, one or more emigrants threatened the marshal and showed contempt for his authority.

Although the number of "combatants" in this fracas was small, the tenor of the surviving accounts is that this encounter was explosive and that some Cedar leaders and settlers reacted with alarm. Some militia leaders there reacted with hostility.

Senior militia and religious authorities in Cedar City (who in most cases were one and the same) quickly leapt to a conclusion. With the war climate skewing their interpretation of events, they concluded that the emigrants were hostile and in league with U.S. troops then thought to be invading southern Utah. (7) One statement comes from Major Haight's adjutant, the young Welshman Elias Morris. Morris avowed that the emigrants were allied with the advancing troops "as they [the emigrants] themselves claimed."

(8) Cedar City militiaman Charles Willden swore in an affidavit that "the United States troops were on the plains en route to Utah, that they and said [Arkansas] Company would go on to the Mountain Meadows, and wait there until the arrival of said troops into the Territory and would then return to Cedar and Salt Lake [and] other towns through which they had passed in said Territory and carry out their threats. . . ." In the same fashion, militia commanders conflated the threatening U. S. troops they imagined were in the eastern mountains with the emigrants in their midst.

(9) Moreover, the orders they sent to other settlements conveyed their distorted views. Thus, several days later and in response to orders, Mormon southerners from Washington moved toward Mountain Meadows. Riding along, James Pearce later recounted, they discussed the reports that had originated in Cedar City. "The talk was [about] the party, that some of them said they had helped to kill old Joe Smith and they were going to California to raise some troops. They was going down below for a thousand men, going to get men already armed, and would come back and drive the Mormons out and take their means from them."

(10) After the confrontation in Cedar City, Bishop Philip Klingensmith, also a private in one of the militia platoons, confessed that he was present at a council meeting at which the "destruction" of the emigrant train was debated. (11) As a militia leader in the south, Major John D. Lee confessed to believing that "the killing of [the Arkansas company] would be keeping our oaths and avenging the blood of the Prophets." (12) Major Lee averred that the emigrants were so depraved that there was not "a drop of innocent Blood in their whole Camp."

Talk of "no innocent blood" is significant for two reasons, first, it is strong evidence of "devaluing," which some argue is a necessary condition in mass killings. Second, it is an extreme form of denunciation indicating that the actors may be shifting from fighting words to hostile actions.

Planning Hostile Action Against the Emigrant Company

September 4-6, 1857

(13) While some militiamen later acted out of a sense of military or religious compulsion, others' actions were not mere servile obedience to orders but active cooperation and collaborative effort. Thus, in describing the night meeting with Major Isaac C. Haight at the iron works in Cedar City in which they laid plans to incite Indian attacks on the emigrant train, Major Lee confessed, "We agreed upon the whole thing, how each one should act. . . ."

(14) Moreover, Lee admitted to the conspiratorial setting of his meeting with Major Haight in Cedar City: late at night at the iron works, wrapped in blankets against the cold, away from prying eyes and ears. (15) John D. Lee admitted receiving orders to convey to his son-in-law, Carl Shirts, "to raise the Indians south, at Harmony, Washington and Santa Clara, to join the Indians from the north, and make the attack upon the emigrants at the Meadows."

(16) Returning home to Fort Harmony, probably early Saturday morning before daylight on September 5, 1857, Major Lee encountered some Paiute bands from around Cedar City lead by subchiefs Moquetas and Big Bill. According to John D. Lee, their orders were to "follow up the emigrants and kill them all" and they solicited Lee to "go with them" to the Mountain Meadows and "command their forces." Declining temporarily, Lee told them that he had orders to "send other Indians on the war-path to help them kill the emigrants" and he had to "attend to that first." (17) Lee further admitted telling them, "I would meet them the next day and lead them."

Inciting Paiute Indians to Assemble at the Mountain Meadows

September 4-8, 1857

(18) Arriving at his home at Fort Harmony, John D. Lee found his son-in-law, Carl Shirts, a 2nd Lieutenant in a platoon in Lee's 4th Battalion of the militia. Lee told Shirts "what the orders were that Haight had sent to him." According to Lee, after some initial hesitation Shirt left to "stir up the Indians of the South, and lead them against the emigrants."

(19) Later, Indian interpreter Samuel Knight, a private in Lee's 4th battalion, received similar orders. Knight admitted directing the band of "Piedes" (Southern Paiutes) on the Santa Clara "to arm themselves and prepare to attack the emigrant train." (20) Meanwhile, in Cedar City, 2nd Lieutenant Nephi Johnson admitted attending a meeting with Isaac C. Haight before the massacre in which Haight told him of the plan to "Gather up the Indians And Distroy the train of Emigrants Who Had passed through Cedar. . . ."

(21) The campaign to incite the Southern Paiutes was successful: The estimates of the number of Paiutes at the Mountain Meadows ranged from 300 to 600. Nephi Johnson, an Indian interpreter and 2nd Lieutenant in Cedar City's Company D, estimated that they incited 150 Paiutes to attack in the main massacre. (22) Regarding the priority the militia placed on maintaining solidarity with local bands, Major John Higbee recollected that "every means in right and reason was used to secure the Friendship of the surrounding Tribes of Indians. . . ." (23) In his talks with Major Haight, Nephi Johnson conceded suggesting that the attack on the emigrants should be made farther south at Santa Clara Canyon instead of Mountain Meadows.

The First Attack

Monday, September 7

(24) Several men besides John D. Lee admitted being present in the valley of the Mountain Meadows on the morning of Monday, September 7. At daybreak, Private David Tullis along with Jacob Hamblin's adopted Indian boy, Albert Hamblin, were each in bed in the northern valley when they heard gunfire signaling the first attack on the camp in the southern valley. (25) "After the train had been camped at the spring three nights," Albert recollected, "the fourth day in the morning, just before light, when we were all abed at the house, I was waked up by hearing a good many guns fired. I could hear guns fired every little while all day until it was dark." (26) David Tullis heard the "firing on Monday morning, and four or five mornings afterwards." Tullis and Albert Hamblin admitted that they did not intervene, seek help or notify others.

The first attack was a sudden assault that left seven emigrants dead and sixteen or seventeen wounded; three more would die of their wounds during the siege. (27) John D. Lee admitted that he was "the only white man there [at the siege site]." (28) During one Indian attack, Lee was so close to the action that emigrants' bullets grazed his shirt and hat. (29) Later during the four-day siege, Lee was so close to their camp that he was seen by the emigrants who had raised a white flag. (30) Also Lee was seen at close range by two emigrant children who were sent out to converse with him.

Militia Reinforcement Sent to the Meadows

(31) Meanwhile on Monday morning in Cedar City, Private Joseph Clews was assigned to carry an express to Amos Thornton in the hamlet of Pinto near the Mountain Meadows. Fulfilling these orders, Clews and his companion rode on to the Meadows. Clews was the first Cedar City militiaman to admit that he was at the Meadows on Monday evening.

(32) Back in Cedar that day, Major John Higbee admitted mustering a detachment of militiamen and heading west toward the Meadows. Around sundown that evening, militia private and Cedar City herdsman Henry Higgins, herding the community stock in the common field, observed Major Higbee with a detachment of approximately twenty-five armed men in wagons or on horseback.

(33) In the enveloping crisis, many militiamen and Indian interpreters were compelled to obey military orders or face severe repercussions. They feared punitive measures from the military officers in Cedar City if they disobeyed. (34) Thus, Nephi Johnson resisted entreaties from Indian runners that he go to Mountain Meadows to interpret in place of Lee's Indian boy who "Lied to them so Much" that "they were tired of [him]." But when militia couriers arrived at his ranch, "they said to me that [Major] Haight said to them that I must come whether I Wanted to or Not. That He Would tell me what He wanted when I arrived at Cedar City."

(35) Some militiamen understood that they were being assigned as a burial detail to bury the dead. Others, however, had a different understanding. According to the reminiscent account of Private Ellot Willden, when he and the unidentified members of his party first rode to Mountain Meadows "they were to find occasion or something that would justify the Indians being let loose upon the emigrants. . . ." (36) Later that week, Indian interpreter Nephi Johnson, was given a reasonably accurate account of white-incited Indian attacks on the emigrants and that his mission was "to settle a difficulty between John D. Lee and the Indians. . . ."

(37) Philip Klingensmith, the bishop in Cedar City and a militia private, admitted that the local militia was called out "for the purpose of committing acts of hostility against [the emigrants]." Further, he conceded that this call was "a regular military call from the superior officers to the subordinate officers and privates of the regiment at Cedar City and vicinity."

(38) Over the weekend, Samuel Knight had taken an express from the Meadows to Fort Clara (and possibly Washington). He admitted that on Monday evening as he and other militiamen from Washington and Fort Clara rode toward the Meadows, they met the battalion commander of their region, Major Lee. On Tuesday, Knight and the others from the two southern settlements arrived at Mountain Meadows.

(39) Meanwhile on Tuesday morning, as Private Joseph Clews rode east toward Cedar City from Mountain Meadows, he encountered Higbee and his contingent headed west to Mountain Meadows. Higbee ordered Clews to fall in with his unit. They arrived at the Meadows that afternoon. (40) After assessing conditions and meeting in council to deliberate, Major Higbee admitted that he returned "at once to Cedar [City]" and "reported to Major Haight that [the] emigrant company was not killed as Lee['s] express had stated the day before, but were fortified and were under a state of siege. . . ." Although Higbee did not see Colonel Dame, he conceded that the purpose of his express was "to inform Col. William H. Dame, Commander of [the] Iron Military District, [of] the conditions of things at [Mountain Meadows]."

The Siege at Mid-Week

During the week, Major John M. Higbee recalled, he observed that two or three militiamen were "painted like Indians." (41) At least one of the two militia camps was within sight and earshot of the emigrant camp. From that militia camp, Sergeant Samuel Pollock admitted, he and other militiamen observed Indians firing on the emigrant camp but took no action to intercede.

(42) After the sudden attack on Monday morning, September 7, the emigrants had taken defensive action to afford themselves better protection. They circled their wagons, dug holes around their wagon wheels, lowered their wagon boxes and built other crude defensive fortifications. Observing these fortifications and the Indians' ineffectual fighting on Wednesday, September 9, Major Lee reluctantly concluded that the Indians and the emigrants were at a standoff. (43) The impasse created a crisis for militia commanders. "We knew," Major Lee admitted, "that the original plan was for the Indians to do all the work, and the whites to do nothing, only to stay back and plan for them, and encourage them to do the work. Now we knew the Indians could not do the work, and we were in a sad fix."