Samuel Knight

Samuel Knight, his personal and family background, and his involvement in and statements about the Mountain Meadows Massacre

Samuel Knight

1832-1910

Contents

- 1 Biographical Sketch

- 1.1 Early Life in Missouri and Illinois

- 1.2 Migration to Utah

- 1.3 Indian Interpreter in the Southern Indian Mission

- 1.4 In the Iron Military District: Private Samuel Knight, Company H, John D. Lee's 4th Battalion, Fort Clara

- 1.5 Immediate Aftermath of the Massacre

- 1.6 Scouting to Encounter the U.S. Army in 1858

- 1.7 In Jacob Hamblin's Expeditions to the Hopi Mesas

- 1.8 The Black Hawk War (1865-68) and the Mormon-Navajo War (1868-1870)

- 1.9 Later Life in Santa Clara

- 1.10 Testifying in John D. Lee's Second Trial, 1876

- 1.11 Later Statements about the Massacre

- 1.12 Final Years

- 2 References

- 3 External Links

Biographical Sketch

Early Life in Missouri and Illinois

Born in 1832 in Jackson County, Missouri, Samuel Knight was descended from New England Yankee stock. His grandfather, Joseph Knight, and his father, Newell Knight, had been early supporters of the Mormon founder Joseph Smith in upstate New York. They had been part of the "Colesville Branch" that moved in 1831 to Jackson County in western Missouri. In 1833, conflict with the original settlers in Jackson County drove the Mormon newcomers into northwestern Missouri.

While they squatted along the river bottoms, Knight's mother died shortly after childbirth. His father married Lydia Goldthwait and the family briefly settled in Ray County in northwest Missouri but in 1836 were pressured to leave. They homesteaded at Far West in nearby Caldwell County where in 1838 more armed conflict ensued between the original settlers and the Mormon newcomers. Knight's father participated in the militia actions around Far West. In early 1839, after their ouster from western Missouri, they moved to Commerce, Illinois, then upriver to Nauvoo on the Illinois frontier.

Migration to Utah

The Knight family departed Illinois in 1846 and were among the vanguard company that wintered on the traditional lands of the Ponca Indians in present-day Nebraska. There his father died in early 1847. To avoid possible legal claims to him from his mother's family, Knight's stepmother sent him ahead on the trail.

Thus, Knight, 14, joined the Abraham O. Smoot - George B. Wallace Company, which was recruiting at the outfitting post on the Elkhorn River west of Winter Quarters, Nebraska. They departed in mid-June on the overland trek. The Smoot-Wallace Company was one of several companies in the so-called Big Company that traveled behind Brigham Young's Pioneer Company that summer. They passed what would later become commonplace milestones on the trail: Fort Kearney, the South Fork of the Platte River, Chimney Rock, Fort Laramie, the Sweetwater River, Independence Rock, Devil's Gate, Green River, Fort Bridger, Bear River, and Weber River. After suffering the usual hardships of overland trail, they arrived in the valley of the Great Salt Lake in late September.

He passed the difficult years of 1847-1850 in Great Salt Lake Valley. In 1850, his stepmother and his half-brothers and -sisters made the overland trek and he was reunited with them that fall.

Indian Interpreter in the Southern Indian Mission

In October 1853, at the age of twenty, Knight was called as an Indian missionary to southern Utah and arrived at Fort Harmony in spring 1854. Indian Mission leader Rufus Allen selected Jacob Hamblin, Thales Haskell, Ira Hatch, Samuel Knight, and Gus Hardy to leave Ft. Harmony and establish a new fort on the Santa Clara. Hamblin, Haskell and Hardy arrived in December 1854; Hatch and Knight arrived early in 1855. Hatch, 19, and Knight, 22, would accompany Hamblin on a number of missions in the future.

After building a diversion dam on the Santa Clara, Jacob Hamblin, Ira Hatch, Thales Haskell, Sam Knight and Dudley Leavitt began building a stone fort on the banks of the Santa Clara Creek and soon began planting cotton which proved successful. News of their success in raising cotton would soon lead to the founding of the Cotton Mission in nearby Washington and St. George.

In 1856, Knight married Danish emigrant Carolyn Beck (1836-1869) and immediately brought her to Fort Clara on Utah's southern frontier.

In the Iron Military District: Private Samuel Knight, Company H, John D. Lee's 4th Battalion, Fort Clara

In 1857, the Southern Indian Mission were headquartered at Fort Clara on the lower Santa Clara River near modern-day St. George, Utah. It was part of the Iron Military District which consisted of four battalions led by regimental commander Col. William H. Dame. The platoons and companies in the first battalion drew on men in and around Parowan. (It had no involvement at Mountain Meadows.) Major Isaac Haight commanded the 2nd Battalion whose personnel in its many platoons and two companies came from Cedar City and outer-lying communities to the north such as Fort Johnson. Major John Higbee headed the 3rd Battalion whose many platoons and two companies were drawn from Cedar City and outer-lying communities to the southwest such as Fort Hamilton. Major John D. Lee of Fort Harmony headed the 4th Battalion whose platoons and companies drew on its militia personnel from Fort Harmony, the Southerners at the newly-founded settlement in Washington, the Indian interpreters at Fort Clara, and the new settlers at Pinto.

Samuel Knight, 24, was a private in company H in John D. Lee's 4th Battalion. Other Indian interpreters in Lee's geographically sprawling battalion were Dudley Leavitt, Oscar Hamblin, and Amos Thornton (Fort Clara), Carl Shirts (Fort Harmony), and David Tullis (Pinto).

In mid-1857, to avoid the summer heat on the lower Santa Clara, Samuel Knight, Jacob Hamblin, David Tullis and others were homesteading a mountain ranch at the Mountain Meadows. In early August, Knight's wife Caroline gave birth to their first child. His wife was seriously ill and they remained there for several months while she recuperated from her difficult delivery.

Around Saturday, September 5, having received orders from Cedar City, Knight carried orders south to Fort Clara (and perhaps Washington) to incite Indians on the lower Santa Clara to gather at Mountain Meadows. A militia contingent from these southern communities was also to muster to Mountain Meadows. See A Basic Account for a full description of the massacre.

On Monday, September 7th in the evening, following the first attack on the Arkansas emigrants at Mountain Meadows, Knight and other southern militiamen met Major John D. Lee south of the Meadows, joined him and moved up to the Meadows the following day.

They arrived at Mountain Meadows around noon on Tuesday, September 8. Knight went back to the northern end of the valley to Jacob Hamblin's cabin where his wife was convalescing in their wagon box. The rest of the militiamen from the southern settlements camped in a separate encampment from the Cedar City detachment which had already arrived and set up their own encampment.

On Friday the 11th, Major John D. Lee recruited Knight and Sergeant Samuel McMurdie to drive their wagons to the emigrant wagon circle and carry away young children and wounded adults. As the emigrants filed out of their wagon circle, John D. Lee with McMurdie and Knight carrying the small children and several injured adults were in the lead. Some distance behind trailed the women and children. Bringing up the rear were the emigrant men, shadowed by a militia guard unit from Cedar City.

What occurred in the final massacre at the head of the line is contested. Samuel McMurdie and Samuel Knight testified in Lee's second trial in 1876 that Lee shot the injured adults in McMurdie's wagon. Knight said he was calming his fractious horses which were unnerved by the shooting. When McMurdie was questioned about his role, he invoked his right against self-incrimination. In Lee's later published statements he denied any killing, saying his gun had jammed and that McMurdie and Knight had shot the injured adults. But before his execution, Lee was more forthcoming; his gun had jammed after he had shot several of the adults.

After the final massacre these two wagons carried the seventeen surviving children to Hamblin's ranch where Rachel Hamblin tried to calm them as best she could.

Immediate Aftermath of the Massacre

Having induced local Indians to join them massacring the Arkansas company, the Iron County militia now found that they had lost control of them. Following behind the Arkansas train was the Dukes-Turner Company which fell under attack at Beaver. After arriving in Cedar City, Dukes and Turner hired Ira Hatch, Oscar Hamblin and Nephi Johnson to guide them through. Meanwhile, Jacob Hamblin sent Dudley Leavitt and Samuel Knight to conciliate the Paiutes in Nevada. When the Dukes-Turner Company arrived near the Muddy River in Nevada, Leavitt convinced Dukes and Turner to release stock to the Paiute Indians. Controversy still swirls around this episode. Had Leavitt and Knight used the Paiutes to rob the train of its livestock, or, by appeasing the Paiutes with cattle, did they save the lives of those in the Dukes-Turner train?

Scouting to Encounter the U.S. Army in 1858

In March 1858, Knight was in the patrol to southern Nevada with Jacob Hamblin, Dudley Leavitt, Ira Hatch and others to scout for the approach of the U. S. Army from the West Coast.

Arriving on the lower Colorado River, they reconnoitered the progress of Lt. Joseph Ives’s historic steamboat voyage up the river. They encountered Paiutes and Mohaves and Thales Haskell made contact with the steamer. Occurring in the midst of the Utah War when distrust was high, each side spied on the other and harbored mutual suspicions.

In Jacob Hamblin's Expeditions to the Hopi Mesas

In fall 1858, Jacob Hamblin decided to visit the Indians who intrigued him so much, the Hopi. Over the years he would make many trips to the Hopi Mesas and Navajo lands and Knight accompanied him in 1858, 1861 and 1873. Following the lead of Jacob Hamblin, many Indian interpreters would eventually move to Arizona to pursue their interest in the Hopi. Knight, however, remained in southern Utah and worked primarily among the "Piedes," or Southern Paiutes.

From October to December 1858, Hamblin undertook his first historic crossing of the Colorado River to travel though Navajo lands to the Hopi Mesas in northeastern Arizona. Ira Hatch, Samuel Knight and Dudley Leavitt were with Hamblin in a party of fourteen on this first journey. Arriving at the Colorado River, they scouted the area at the mouth of the Paria River (later Lee’s Ferry) but were unable to cross. Traveling some miles farther east, they forded at the Ute Ford, or Crossing of the Fathers.

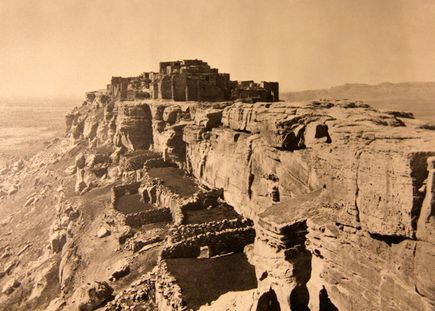

Traveling up Navajo Canyon they emerged and crossed the plateaus and arrived at Old Oraibi on Third Mesa in Hopi land.

Next, they visited Sichomovi and Walpi at First Mesa. Returning, they passed through Mishongnovi at Second Mesa. Trading for what supplies the Hopis could afford to part with, they set out on their return.

Retracing their steps they crossed the Colorado. Running short of supplies north of the river, they nearly starved to death. Feeling weak and ill, Sam Knight was left behind and nearly froze to death. In desperation, they killed and ate Dudley Leavitt’s horse to stay alive. They made it back to Ft. Clara on the Santa Clara stream without loss of life.

In fall 1860, Hamblin set out again for the Hopi Mesas. This was his third crossing of the Colorado. Among those who journeyed with him was George Smith, Jr., the son of Mormon leader George A. Smith. After crossing the Colorado River at the Ute Ford, or Crossing of the Fathers, they proceeded as far as Quichintoweep near Moenkopi Wash. There hostile Navajos fatally wounded George Smith, Jr. and he died within hours. The party was forced to abandon his body and retreat without reaching the Hopi Mesas.

In February 1861, Hamblin returned to Arizona to recover the remains of George Smith, Jr. Sam Knight, Amos Thornton, William Stewart and others accompanied him on this fourth crossing of the Colorado River. Following their previous route they arrived at the Ute Ford and crossed to the south of the river. Traveling generally southeast, they passed the Inscription House ruins. Fearing to go farther into Navajo lands, they sent their Paiute companions ahead to retrieve what they could of Smith’s remains. Then they returned to Utah via the Ute Ford without going to the Hopi Mesas.

In the Black Hawk War (1865-68) raiding parties of Utes, Paiutes and Navajos drove off Mormon livestock throughout the region and led to some pitched battles between the allied tribes and Mormon militias. A peace treaty in 1868 brought most of the depredations in Utah to a close, except in southern Utah where Navajos continued raiding across the Colorado River into lands occupied by the Mormons.

There were a series of tenuous peace treaties with the Navajos in 1870, 1871 and 1872 but the McCarty affair (Grass Valley murders) brought further unrest in 1873-74 until a final peace treaty was achieved. Samuel Knight made at least one trip with Jacob Hamblin to eastern Arizona to pursue peace negotiations with the Navajos.

Later Life in Santa Clara

In 1862, when Swiss emigrants moved to Santa Clara in southwest Utah, Knight and his family was among the few native-born Americans to remain.

In the mid-1860s, Knight, Dudley Leavitt and others moved their families to Clover Valley and Meadow Valley in modern Lincoln County, Nevada. There they remained for several years. However, the outbreak of the Black Hawk War in 1865 eventually caused Mormons to abandon many unprotected outposts. Knight and his family returned to Santa Clara in southwestern Utah where he resided for the remainder of his life.

By the time of the death of his wife Carolyn in 1869, she had borne him six children. Following her death, he married Dudley Leavitt's sister, Laura Melvina Leavitt (1851-1922), Utah born with Canadian and New England roots, who bore him ten children. Over the years, Laura Knight made a notable contribution to the community as a midwife and nurse.

Testifying in John D. Lee's Second Trial, 1876

In September 1876 during the second trial of John D. Lee, the prosecution called former Iron County militiamen Joel White, Samuel Knight, Samuel McMurdie, Nephi Johnson, Laban Morrill, and Jacob Hamblin to testify against Lee. Knight's testimony can be found here.

His only polygamous marriage was in 1888 to a Missouri-born widow, Susan Charlotte Nanney Hunt (1832?- ?), just two years before the Mormon Church's Manifesto that officially ended the practice.

Later Statements about the Massacre

In the 1890s and the early twentieth century, Knight gave several important interviews and statements concerning the massacre. With the exception of some statements contained in third-party journals, all of Samuel Knight's written statements and affidavits have now been published in Turley and Walker, Mountain Meadows Massacre: The Jenson and Morris Collections. His trial testimony in the 1876 trial of John D. Lee is available online.

Final Years

He lived on in Santa Clara, earning his livelihood as a farmer and rancher and continuing to work with the local Paiutes. He spent more than 50 years in Santa Clara. He died in 1910 and was buried there, survived by his second wife Laura and eleven children (see photo of his second family, below).

At the time of his death, his obituary noted that he was known for recounting his early years in Missouri and Illinois where he and his family had been driven from their homes on four occasions, an indication of the persistence and power of these early life experiences to shape Mormon memory and identity.

In Todd Compton's excellent new biography of Jacob Hamblin, he concluded that Ira Hatch, Thales Haskell, Samuel Knight, Ammon Tenney, and Dudley Leavitt were Hamblin's "irreplaceable supports on these forays into unknown, unmapped, and often inhospitable places.” (Compton, A Frontier Life, 480.)

References

Bagley, Blood of the Prophets, 12, 34, 119, 126, 128, 146, 149, 153-54, 158, 170, 212, 304; Bigley and Bagley, Innocent Blood: Essential Narratives, 111, 259, 314, 347-48, 419-21 (statement), 457, 467; Bradshaw, ed., Under Dixie Sun, 25, 30, 36, 62, 130, 146, 148, 150, following 152 (photo), 158, 172, 214; Brooks, The Mountain Meadows Massacre, 74, 83, 107, 121, 123, 197; Brooks, ed., Journal of the Southern Indian Mission, 2, 7, 67, 78, 118, 120; Fielding, ed., The Tribune Reports of the Trials of John D. Lee, 215-16, 218-19; Hartley, They Are My Friends, 6, 86, 117; Hartley, Stand by My Servant Joseph, 154, 195, 332-33, 355; Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Latter-day Saints, 776 (Santa Clara Ward); Knight, Lydia Knight’s History, 35, 72, 90-91, 100; Larson, I Was Called to Dixie, 38, 44, 52, 102, 159, 161, 541; Larson, Diary of Charles Lowell Walker, Vol. II, 835, 872; Larson, Erastus Snow, 315, 384; Lee, Mormonism Unveiled, 228, 238, 241, 242, 243, 250, 252, 380; Lee Trial transcripts; Little, Jacob Hamblin, ; Moorman and Sessions, Camp Floyd and the Mormons, 133-34, 136; New.FamilySearch.org; Robinson, ed., History of Kane County, 3; Solomon, Joseph Knight, 1, 20, 23, 59, 78, 89, 95, 115; Turley and Walker, Mountain Meadows Massacre: Jenson and Morris Collections, 97, 115, 202, 220, 262-64 (biographical sketch), 265-66, 270, 296, 320-322 (affidavit); Walker, et al, Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 6, 140-41, 150-51 (brief sketch), 152, 161-62, 193, 195-98, 204, 213, Appendix C, 254, 259, Appendix D, 265; Whittaker, History of Santa Clara, Utah, 24-25, 26, 32, 43, 46, 58, 85, 89, 120, 122, 133, 134-39 (biographical sketch), 211, 281, 370-71, 560.

For full bibliographic information see Bibliography.

External Links

For further information on Samuel Knight, see:

- Samuel Knight's testimony in the 1876 trial of John D. Lee is at: http://www.mtn-meadows-assoc.com/knight.htm

- http://records.ancestry.com/Samuel_Knight_records.ashx?pid=17695609

- http://www.geni.com/people/Samuel-Knight/6000000000875614129

- http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=pv&GRid=42044

- http://earlylds.com/getperson.php?personID=I17113&tree=Earlylds

- http://mountainmeadowsmassacre.org/appendices/appendix-c-the-militiamen

- http://wchsutah.org/people/samuel-knight.php

- http://wchsutah.org/people/samuel-knight1.pdf

- http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~knight57/direct/knight/aqwg578.htm#11101

- For the early Southern Indian Mission, see http://wchsutah.org/miscellaneous/indian-mission.php

Further information and confirmation needed. Please comment or contact editor@1857ironcountymilitia.com.